- Home

- S. E. Lynes

The Pact_A gripping psychological thriller with heart-stopping suspense Page 3

The Pact_A gripping psychological thriller with heart-stopping suspense Read online

Page 3

‘Mummy?’

‘Rosie?’ I said, trying but failing to keep the panic out of my voice. ‘Are you OK, baby girl? Is everything OK?’

‘Mum, I’m fine. I just forgot my phone.’

‘Again? What have I said about going out without your phone?’

‘Oh my God, stop stressing.’ Your teenage irritation was palpable. ‘I’m just borrowing Abed’s, it’s fine. They let us out early, that’s all.’

‘Oh, thank God.’ I pressed the phone to my chest a moment and sighed before I put it back to my ear. ‘Sorry, baby. As long as you’re OK. I’m on my way, all right? I’ll be there in ten minutes. Well, twenty.’

‘It’s not that, Mum. Just listen a sec, will you? I had to call because… well, because guess who got the lead?’ You giggled, and I knew instantly, of course.

‘Erm, let’s see,’ I said, stalling. ‘Toby Marsh?’

You giggled again. ‘No-o.’

‘Sarah Peters? Maggie whatsherface? No, I’m joking.’ I paused. ‘It was Stella Prince, wasn’t it?’

You knew I was teasing but you had to say it anyway – you were like a shaken-up bottle of lemonade. ‘I did!’ Cap off, out it fizzed. ‘Me! I got it! I’m going to be Little Red Riding Hood!’

‘You’re joking?’

‘I’m not!’

‘Does that mean I have to make you a cape now? Couldn’t you have got something easier, like a tree or something?’

You laughed then, a big loud hahaha! – pure, delicious, unguarded. ‘You won’t! They have proper wardrobe and everything. There’s a lady at the theatre that does it; it’s, like, her job. They said to not have a haircut between now and Easter, but that’s about it.’

Your lovely russet hair. Hair to make people turn in the street. Your father’s colouring. My God, how ecstatic he would have been, I thought. How filled up, how proud. ‘My little red fox,’ he would have said, and fifteen or not, he would have picked you up and spun you around for joy.

‘I still think Toby Marsh should have got it,’ I said.

We were both helpless with laughter now, caught up in the wonder of the moment and all it meant, all that lay behind it: the accident and its terrible aftermath. We both knew, I think, that we were at the top of some kind of hill, looking down on what had been the most arduous of climbs. We couldn’t believe that we were there, at the summit. We had only to raise our eyes to see the view clear and blue before us. We had only to step into it and it would be ours.

I found myself blinking back tears.

‘Mum?’ you said. ‘Are you still there?’

‘It’s amazing, baby girl,’ I managed to say. ‘Seriously. Wait till I tell your auntie Bridget. She’ll be over the moon. I’m so very proud of you.’ I bit my lip, wiped my wet cheek with my free hand. ‘What I mean is, I’m proud of you for fighting those nerves. That took guts.’

‘Thanks. I did the exercises like Auntie Bridge said and I… I just went for it.’

‘That’s brilliant. And you’re still at the Cherry Orchard?’

‘I’m just at the entrance. The others are going for the bus. There’s, like, five of us. The 33 goes right to the end of our road.’

‘No, no. I’ve literally already got my bum in the car. Wait there, OK?’

‘But, Mum, I can get the bus!’

‘No, baby girl. Stay there, I’m coming for you.’

You sighed. ‘OK.’

‘Don’t go off anywhere, will you?’

‘I won’t.’

I rang off, unable to wipe the smile from my face. You, who had been so quiet for so long, you were blossoming once again like… like cherry blossom – why not? Beautiful and white and bold on the tree. I felt your confidence, my love. I’d felt it grow those last few years since you’d joined that theatre. I had allowed myself to believe, or start to believe at least, that the feisty six-year-old you had been, with her dressing-up clothes and her little picnic-tabletop stage, the little Rosie who had been ours before the accident, was back.

And then, months later, when we came to watch you perform, all dressed up and lost in the part and giving it your all, and Emily approached us in the theatre bar afterwards, I was so proud of you that I felt if someone tapped me on the shoulder or whispered something too kind or cruel, I would shatter into pieces on the floor. Your auntie Bridget was proud of you too, of course, but not like me. I’m your mother. There is no one, no one who loves you more than I do. No one ever will. No one could.

Blossoms fall, though, don’t they? I didn’t think about that.

Nine

Bridget

‘May I be allowed to congratulate the marvellous Little Red?’

That’s what she says, the woman, as she limps towards them across the theatre bar. Her huge eyes blink behind strong lenses, a slightly manic smile on her face, the programme rolled up in her hand. Bridget half expects her to start bopping them all on the head with it.

To Bridget’s surprise, Rosie doesn’t clam up as she usually does in front of strangers.

‘Thank you,’ she says, all smiles, offering her hand to shake. ‘That’s really kind.’

‘Emily,’ the woman says. ‘Emily Wood.’

‘I’m Rosie Flint, and this is my mum, Antonia, and my auntie Bridget.’

‘Lovely, how lovely.’

As they say their hellos, the lenses in Emily Wood’s glasses flash under the downlights.

‘Now,’ she says, hands on hips, ‘I won’t beat around the proverbial; I’ll come right out and say it. I’m wondering if Little Red here would be interested in a conversation about possible representation.’ The woman is as rambunctious as Toad of Toad Hall, as hearty as Father Christmas.

‘Wow,’ Toni says, glancing at Bridget. ‘I was not expecting you to say that.’

Rosie meanwhile has gone pink. When Bridget catches her eye, her smile reaches her ears.

‘I’m in the business, as they say,’ Emily goes on, ‘but I’m moving from acting to agency, as it were. Scouting for talent, I suppose you’d call it.’ She leans back and chuckles – a real old-lady chuckle. ‘Scouting for talent, what on earth do I sound like? A silly moo, that’s what.’

Bridget can’t look at her niece or her sister. Knowing she has to be serious always makes her lose it, and if she gets the giggles now, she knows she won’t be able to stop. At Central, she had a reputation for corpsing, especially during scenes involving love or death.

‘Scouting,’ Emily continues. ‘Sounds like something to do with tents and knots and dyb dyb dyb, doesn’t it?’ She chuckles again, rounds it off with a kind of hoot and a sigh.

Bridget focuses on her boots, bites her bottom lip against growing hilarity, the increasing and horrific possibility of a full-on snort. The woman is crazy. Batshit, Rosie would say – will say, Bridget is sure, once they hit the privacy of the van. As for the woman, she’s borderline hysterical. She pushes up her glasses and draws her finger under her eyes to wipe away her stray tears.

‘Antonia,’ she says, letting the glasses fall back onto her nose. ‘Your daughter really is the full package.’

‘You make her sound like cheese,’ Toni says, laughing. ‘Or drugs!’

Bridget and Rosie exchange a smirk. Toni can be heroically tactless sometimes.

‘Sorry, yes, quite,’ Emily says, apparently not fazed in the slightest. ‘Cheese, indeed. What I mean is, she has the lot. She’s as beautiful as a peach – look at her skin! And she really can act. Her singing voice is… well it’s nothing a voice coach can’t fix. Does she have any other talents?’

‘She has a brown belt in taekwondo.’ Toni nods at Bridget. ‘Her auntie takes her every week.’

‘Oh for God’s sake, Mum,’ Rosie mutters, rolling her eyes.

Bridget keeps her mouth shut, as she always tries to when things have nothing to do with her. She’s been careful to stay an aunt, especially since she had to move in. This conversation is about Rosie, and Toni is Rosie’s mother, no one else.

/> ‘No, that’s good, that’s good.’ Emily closes one hand into a fist and swipes the air. ‘It shows athleticism. Fitness is so important in this game. And the martial arts are marvellous for discipline of mind and body.’

‘And self-defence,’ Bridget adds – can’t help herself.

‘Self-defence indeed.’ Emily blinks at Bridget a moment. In those glasses, the effect is of a fish stunned by a flashlight. Blink! She turns back to Rosie and smiles. ‘Yes. Really. The whole package.’

The crowd is dispersing, the hubbub quieting. Emily tells them that she trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama. Bridget almost chips in to say that so did she, and ask Emily which year, but again, it’s Rosie’s moment, so she keeps shtum.

‘I spent most of my career in the theatre,’ Emily says. ‘Character roles mainly, once the old beauty faded. Some television – Casualty and twice on The Bill – but that was when I was younger and prettier. The television work has dried up over the last ten years or so. Plus my dicky hip. Theatre work is so demanding physically, so I said to myself, Emily, I said, it is time for a change.’

‘Do you have a business card or anything?’ Toni says. ‘It’s just that I really need to get this little girl home and to bed.’

‘Of course. Silly moo, wittering on. Yes, yes.’ She digs around in her handbag. ‘I don’t expect you’ve thought about anything like this, and that’s fine. You’ll want to take a moment, I’m sure, but I think I could get Rosie a lot of work. Commercials at first, mostly, I’ll be perfectly honest. They’re not art, but they pay well. Obviously it won’t be Steven Spielberg straight away, but it won’t take long for this one to get noticed, mark my words. She would need a headshot of course, but I can arrange that.’ She throws up her hands. ‘Listen to me, getting ahead of myself. Shut up, Emily, don’t frighten the horses!’ She hands a card not to Toni but to Rosie.

‘Rosie,’ she says. ‘Such a pretty name. So feminine, and perfect for a famous actress, wouldn’t you say? And Flint. Flint is good too – shows strength, a cutting edge, a romantic heroine!’

Rosie giggles. Bridget can tell her niece thinks Emily’s a bit bonkers too. She will definitely imitate the woman once they get home: the frequent blinking, the jolly-hockey-sticks turns of phrase, her constant chuckling. But Bridget has begun to wonder if this last is a sign of shyness, no more than Emily’s way of being in the world, and the thought softens her. Everyone has to find their way of being in the world, don’t they? No one knows that more than Bridget.

‘We should go,’ Toni says, throwing out her hand to shake. ‘Nice to meet you, Emily.’

Seeming not to have heard, Emily traces her forefinger across the card. ‘Into the Light Agency,’ she says. ‘That’s the website address. Some small miracle there, I can tell you. Emily Wood is not exactly known for her technical savvy, to put it mildly. But do have a perusal. If you think you’d like to work with Madame Belle, aka moi, there’s an email on the old calling card there.’ For the second time she throws up her hands. ‘Stop talking, Emily! Rosie, my dear, you must be tired after your magnificent performance. Antonia, Bridget, lovely to meet you both. Goodnight, all. Bonne nuit. Buenos… nottes, noches, or whatever they say in Timbuktu.’ She raises her hand in a wave, blinking all the while. ‘Enjoy the rest of your evening.’

Off she goes, a lopsided heel-toe, heel-toe, her white-grey hair fading out of the theatre and into the night.

Ten

Rosie

I can’t get up off… I have to get up off the seabed. I’m… Shame. I’m ashamed. I’ve done something very bad, something shameful that’s making my stomach tie itself up in knots. Mummy? I’m sorry. I’m sorry, Mum. Am I awake? Emily? Auntie Bridge?

Hey, Squirt. Did you remember your ankle support?

Auntie Bridge! That’s my auntie! That’s her voice!

Where am I? When is this?

Course. I put it on in the flat. That’s me! That’s my voice!

I can see my legs: crossed, white baggy trousers. My blue Doc Martens on the dashboard – the left on the right, the right on the left. We are in Auntie Bridget’s van. We so are because I can hear the rattle of the engine, can smell her vanilla air freshener. Fags, a bit, underneath.

You… you’re not with us, Mummy. You’re probably at home because it’s the evening and you don’t go out, so you’ll be lying on the sofa watching some Netflix series.

Ankle support… white baggy trousers…

Auntie Bridge must be taking me to taekwondo. She always takes me. She stays and watches and shouts Yes! or Get in, girl! when I do a good kick or something, which is so embarrassing. I tell her to shush, but I don’t mind really ’cos the others say she’s a legend. All my friends say she’s a legend. Your auntie’s so cool, they say and I’m like, So?

I have my kit on, my brown belt tied round my waist. I know taekwondo is good for strength and self-defence and everything, but secretly I like it because it’s given me abs. Naomi is jealous of my abs. She always pokes me in the stomach and says, That’s just freaky. I have Instagram abs #nofilter.

Reckon you could still kick someone in the neck? I ask Auntie Bridge. We’re on Twickenham High Street, near Poundland. You know, like, if they were mugging you or something?

She laughs. The van lurches as she changes gear. I could kick you up the arse.

We both laugh. Auntie Bridge is a black belt, second dan, but she doesn’t do it any more. Auntie Bridge has six piercings and seven tattoos. You said if I get a tattoo you’ll bloody kill me. Bloody is your worst swear word. You’re weird about swearing. We’ve got enough stacked against us as it is, is what you say, without a foul mouth on top.

I’m sorry, but that’s just weird.

Auntie Bridge is a grown woman… grown woman… groan, woman… I am a girl who thought she was a grown-up. But I wasn’t. I’m not. And now I can’t see you, Mummy. I don’t know where you are…

Everything slots into place; everything comes around. Auntie Bridge has this tattoo on the inside of her wrist. Everyone thinks it’s a Celtic sign, but it’s not. It’s an A and a B joined together so that the right leg of the A and the spine of the B are one line.

It stands for Antonia and Bridget, Auntie Bridget says.

Where are we now? When are we?

The Italian café, that’s where. Café Bellissimo. I recognise the chairs. I can see Waitrose out of the front window, further up, towards the station. Auntie Bridge wouldn’t be seen dead in Starbucks because she’s an anarchist. She says that all the big chains are fascists. I go to Starbucks with Naomi sometimes, but I don’t tell Auntie Bridge.

Antonia and Bridget. Antonia – that’s you, Mum, obvs. But everyone calls you Toni. The name Toni is so lame, but the only reason you’re called Antonia is because your dad wanted a boy and he was going to call you Anthony, LOL. But he left Granny Casement literally just after you were born, which is proper savage even though you say you were better off without him because he used to hit Granny and stuff. You say Antonia sounds too posh, but Toni is plain cheesy. Cheesy peas, you say when you’re messing about, or when someone takes a photo. It’s from some old comedy show you used to watch. You hate having your photo taken. Cheesy chips, like we get in Dorset. Remember when we were watching the TV that time and they asked that footballer what his favourite cheese was and he said, Er, melted. We laughed our heads off at that, didn’t we?

I could have a tattoo somewhere you wouldn’t see – on my bum!

Bottom, Rosie. The word is bottom.

Bottom, Puck, Titania. Auntie Bridge was Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, she told me. It was when she was young. Bottom of the ocean… a seabed… Auntie Bridge got that tattoo done when she was twenty. It was her first.

What does it mean, Auntie Bridge? We’re back in Café Bellissimo. Auntie Bridge has her Led Zep T-shirt on; her arm is on the table, wrist face up. The A and the B.

What do you mean, what does it mean? she says. I told you, it’s your mum and

me.

I mean, like, why did you have it done?

Because… Auntie Bridge stops, like she can’t say it. She looks me in the eye, as if she’s deciding whether she should say it or not. I had it done because… well, when I found out about Uncle Eric.

Do you mean with Mummy?

She nods.

You told me about what happened with your uncle, but you never talk about him. Literally never. I didn’t know it was why Auntie Bridge got that tattoo – as in, the exact reason. The way I’m remembering this, that’s how it feels, like I didn’t know that before.

Auntie Bridge looks more serious than I have ever seen her. She looks like she’s going to cry, and she never cries. Interfered, you said, but I don’t think you’ve said that word to me yet. In this memory, I mean. I think you told me later. I know what interfere means. You think I’m a kid, but I’m not. I could get married next year, legally. I could have a child. I could go to the GP and get the pill and they wouldn’t have to tell you because it would be patient confidentiality. There are different types of abuse: verbal, emotional, physical. Sexual. We had a talk about it in PSHE last year. Personal, social, health and economic education. So many abbreviations! GCSE… General Certificate of Secondary Education. PE… physical education. YOLO… you only live once. ROFL… roll on the floor laughing. You like FFS. I read that on a text you sent to Auntie Bridge.

I’m locked out, FFS.

Her reply: Spare key under geranium, you muppet.

You say FFS means for flip’s sake, as if I don’t know. You’re so weird. I’m fifteen not ten, you know.

The water is thick and dark. It’s full of weeds. I’m all alone in the moonlight. There is music. The wind is in my hair.

I’m in Emily’s car. I’m in the passenger seat and she has the roof down. We’re singing along to her tape. Cats the Musical.

Midnight…

I’m being sick into a bucket. Your hand is cool on my forehead. That’s it, you say. That’s it – good girl. You’ll feel better now.

Can You See Her?: An absolutely compelling psychological thriller

Can You See Her?: An absolutely compelling psychological thriller The Housewarming: A completely unputdownable psychological thriller with a shocking twist

The Housewarming: A completely unputdownable psychological thriller with a shocking twist The Lies We Hide: An absolutely gripping and darkly compelling novel

The Lies We Hide: An absolutely gripping and darkly compelling novel Mother

Mother The Lies We Hide (ARC)

The Lies We Hide (ARC) The Women: A gripping psychological thriller

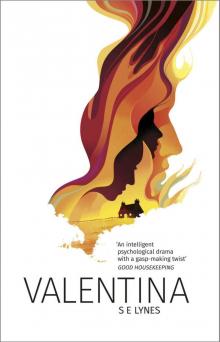

The Women: A gripping psychological thriller Valentina

Valentina The Pact_A gripping psychological thriller with heart-stopping suspense

The Pact_A gripping psychological thriller with heart-stopping suspense Valentina: A Hauntingly Intelligent Psychological Thriller

Valentina: A Hauntingly Intelligent Psychological Thriller